Defining Elements and Attributes

This article gives an

overview of the basic building blocks of XML Schemas and how to use them.

·

Elements

An XML

schema, commonly known as an XML Schema Definition (XSD), formally describes

what a given XML document can contain, in the same way that a database schema

describes the data that can be contained in a database (i.e. table structure,

data types, constraints etc.). The XML schema defines the shape, or structure,

of an XML document, along with rules for data content and semantics such as

what fields an element can contain, which sub elements it can contain and how

many items can be present. It can also describe the type and values that can be

placed into each element or attribute. The XML data constraints are called

facets and include rules such as min and max length.

This tutorial guides you through the basics of the XSD standard

and the examples use the graphical XML Integrated Development Environment (IDE) Liquid Studio.

XML Schema Standards

- XML Schema Definition (XSD) is currently

the de facto standard for describing XML documents and is the XML Schema

standard we will concentrate on in this tutorial. XSD is controlled by the

World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). An XSD is itself an XML document, and

there is even an XSD to describe the XSD standard.

- Document Type Definition (DTD) was the

first formalized standard but has now, in most cases, been superseded by

XSD.

- XML Data Reduced (XDR) was an early

attempt but Microsoft to provide a more comprehensive standard than DTD.

This standard has been phased out in the Microsoft products in favour of

XSD.

- There are also a number of other schema

standards such as Schematron and RELAX NG.

XML Design Tools

The XSD standard has evolved over a number of years, and is

extremely comprehensive and as a result has become rather complex. For this

reason it is a good idea to make use of a graphical XSD design tool when working with XSDs.

XML Development Tools

For those who wish to programmatically work with XML documents,

XML Data Binding is a much easier way to manipulate your documents using an

object oriented approach to enforce the XML schema rules and constraints.

Defining Elements

Tip: To add an Element in the

Liquid Studio graphical XSD view, select menu item Edit->Add

Child->Element (Ctrl+Shift+E) or select the toolbar button .

Elements are the main building

block of all XML documents, containing the data and determine the structure of

the instance document.

An element can be defined within an XSD as follows:

<xs:element name="x"

type="y" />

Each element definition within the XSD must have a 'name'

property, which is the tag name that will appear in the XML document. The

'type' property provides the description of what type of data can be contained

within the element when it appears in the XML document. There are a number of

predefined simple types, such as xs:string, xs:integer, xs:boolean and xs:date

(see XSD standard for

a complete list). Elements of these simple data types are said to

have a 'simple content model', whereas elements that can contain other elements

are said to have a 'complex content model' and elements that can contain both

have a 'mixed content model'. You can also create user defined types using the and constructs,

which we will cover later.

If we have set the type property for an element in the XSD, then

the corresponding value in the XML document must be in the correct format for

its given type otherwise this will cause a validation error when a validating

parser attempts to parse the data from the XML document. Examples of simple

elements and their XML data are shown below:

Sample XSD

|

Sample XML

|

<xs:element name="Customer_dob" type="xs:date" /> |

<Customer_dob> 2000-01-12T12:13:14Z

</Customer_dob> |

<xs:element name="Customer_address" type="xs:string" /> |

<Customer_address> 99 London Road

</Customer_address> |

<xs:element name="OrderID" type="xs:int" /> |

<OrderID> 5756

</OrderID> |

<xs:element name="Body" type="xs:string" /> |

<Body></Body> Note: A type can be defined as a string but not have

any content, this is not true for all data types.

|

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid

Studio as follows:

The

valid data values for the element in the XML document can be further

constrained using the fixed and default properties.

Default means that if no value is specified in the

XML document then the application reading the document, typically an XML parser

or XML Data Binding Library, should use the default specified in the XSD.

Fixed means the value in the XML document can only

have the value specified in the XSD.

For this reason it does not make sense to use both default and

fixed in the same element definition, and is invalid to do so.

<xs:element name="Customer_name"

type="xs:string"

default="unknown" />

<xs:element name="Customer_location"

type="xs:string"

fixed=" UK" />

Specifying Cardinality

Sometimes it is useful to add a constraint to allow an specific number of elements to appear at a specific point in an XML document, this is referred to as cardinality. The cardinality is specified using the minOccurs and maxOccurs attributes, and allows an element to be specified as mandatory, optional, or can appear up to a set number of times. The default values for minOccurs and maxOccurs is 1. Therefore, if both the minOccurs and maxOccurs attributes are absent, as in all the previous examples, the element must appear once and once only.

'minOccurs' can be assigned any non-negative integer value (e.g. 0, 1, 2, 3... etc.), and 'maxOccurs' can be assigned any non-negative integer value or the special string constant "unbounded" meaning there is no maximum so the element can occur an unlimited number of times.

| Sample XSD | Description |

|---|---|

<xs:element name="Customer_dob" type="xs:date" /> | If we do not specify minOccurs or maxOccurs, then the default values of 1 are used. This means there has to be one and only one occurrence of Customer_dob, i.e. it is mandatory. |

<xs:element name="Customer_order" type="xs:integer" minOccurs ="0" maxOccurs="unbounded" /> | If we set minOccurs to 0, then the element is optional. Here, a customer can have from 0 to an unlimited number of Customer_orders. |

<xs:element name="Customer_hobbies" type="xs:string" minOccurs="2" maxOccurs="10" /> | Setting both minOccurs and maxOccurs means the element Customer_hobbies must appear at least twice, but no more than 10 times. |

These XSD definitions can be shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

Defining Simple Types

Tip: To add a Simple Type in the Liquid Studio graphical XSD view, select menu item Edit->Add Child->Simple Type (Ctrl+Shift+S) or select the toolbar button  .

.

.

.

A simple type extends the built in data types such as xs:string, xs:integer, and xs:date, allowing you to create your own data types.

Examples of this are:

- Defining an ID, this may be an integer with a maximum value limit.

- A Postcode or Zip code could be restricted to ensure it is the correct length and complies with a regular expression.

- Defining a field to have a maximum length.

Creating you own types is coved more thoroughly in the Part 2 - Best Practices, Conventions and Recommendations.

Defining Complex Types

Tip: To add a Complex Type in the Liquid Studio graphical XSD view, select menu item Edit->Add Child->Complex Type (Ctrl+Shift+C) or select the toolbar button  .

.

.

.

A complex type is a container for other element definitions, this allows you to specify which child elements an element can contain. This allows you to provide some structure within your XML documents.

Examples of this are:

Here are some simple element definitions:

<xs:element name="Customer" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Customer_dob" type="xs:date" /> <xs:element name="Customer_address" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Supplier" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Supplier_phone" type="xs:integer" /> <xs:element name="Supplier_address" type="xs:string" />

We can see that some of these elements should really be represented as child elements, "Customer_dob" and "Customer_address" belong to a parent element – "Customer". While "Supplier_phone" and "Supplier_address" belong to a parent element "Supplier". We can therefore re-write this in a more structured way:

<xs:element name="Customer"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Dob" type="xs:date" /> <xs:element name="Address" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> <xs:element name="Supplier"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Phone" type="xs:integer" /> <xs:element name="Address" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

What's changed?

- We created a definition for an element called "Customer".

- Inside the <xs:element> definition we added a <xs:complexType>. This is a container for other <xs:element> definitions, allowing us to build a simple hierarchy of elements in the resulting XML document.

- Note the contained elements for "Customer" and "Supplier" do not have a type specified as they do not extend or restrict an existing type, they are a new definition built from scratch.

- The <xs:complexType> element contains another new element <xs:sequence>, but more on these in a minute.

- The <xs:sequence> in turn contains the definitions for the two child elements "Dob" and "Address". Note the customer/supplier prefix has been removed as it is implied from its position within the parent element "Customer" or "Supplier".

So in plain English this is saying we can have an XML document that contains an element <Customer> which must have two child elements <Dob> and <Address>.

Example XML

<Customer> <Dob>2000-01-12T12:13:14Z</Dob> <Address> 34 thingy street, someplace, sometown, ww1 8uu </Address> </Customer> <Supplier> <Phone>0123987654</Phone> <Address>22 whatever place, someplace, sometown, ss1 6gy </Address> </Supplier>

Defining Compositors

There are three types of compositors <xs:sequence>, <xs:choice> and <xs:all>. These compositors allow us to determine how the child elements contained within them will appear within the XML document.

| Compositor | Description |

|---|---|

| Sequence | The child elements in the XML document MUST appear in the order they are declared in the XSD schema. |

| Choice | Only one of the child elements described in the XSD schema can appear in the XML document. |

| All | The child elements described in the XSD schema can appear in the XML document in any order. |

Notes

The compositors <xs:sequence> and <xs:choice> can be nested inside other compositors, and be given there own minOccurs and maxOccurs properties. This allows for quite complex combinations to be formed.

Example

The definitions of "Customer->Address" and "Supplier->Address" are currently not very usable as they are grouped into a single field. In the real world it would be better break this out into a few fields. Let's fix this by breaking it out using the same technique shown above:

<xs:element name="Customer"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Dob" type="xs:date" /> <xs:element name="Address"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> <xs:element name="Supplier"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Phone" type="xs:integer" /> <xs:element name="Address"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

This is much better, but we now have two definitions for address, which are the identical.

Defining Global Types

It would make much more sense to have a single definition for "Address", which could then be used by both customer and supplier. We can do this by defining a complexType independently of an element, and giving it a unique name:

<xs:complexType name="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType>

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

We have now defined a <xs:complexType> that describes our representation of an address, so let's use it. Earlier, when we started looking at elements, we said you could define your own types instead of using one of the standard types such as xs:string or xs:integer, and that is exactly what were now doing.

<xs:element name="Customer"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Dob" type="xs:date" /> <xs:element name="Address" type="AddressType" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> <xs:element name="Supplier"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Phone" type="xs:integer" /> <xs:element name="Address" type="AddressType" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

Hopefully, the advantages are obvious. Instead of having to define Address twice (once for Customer and once for Supplier)

we now have a single definition. This makes maintenance simpler, i.e. if you decide to add "Line3" or "Postcode" elements to

your address you only have to add them in one place.

we now have a single definition. This makes maintenance simpler, i.e. if you decide to add "Line3" or "Postcode" elements to

your address you only have to add them in one place.

Example XML

<Customer> <Dob>2000-01-12T12:13:14Z</Dob> <Address> <Line1>34 thingy street, someplace</Line1> <Line2>sometown, ww1 8uu</Line2> </Address> </Customer> <Supplier> <Phone>0123987654</Phone> <Address> <Line1>22 whatever place, someplace</Line1> <Line2>sometown, ss1 6gy</Line2> </Address> </Supplier>

Notes

Note: Only complex types defined globally (as children of the <xs:schema> element can have their own name and be

re-used throughout the schema). If they are defined inline within an <xs:element> they can not have a name (anonymous)

and can not be reused elsewhere.

re-used throughout the schema). If they are defined inline within an <xs:element> they can not have a name (anonymous)

and can not be reused elsewhere.

Defining Attributes

Tip: To add an Attribute in the Liquid Studio graphical XSD view, select menu item Edit->Add Child->Attribute or select the toolbar button .

An attribute provides extra information within an element. Attributes have name and type properties and are defined within an XSD as follows:

<xs:attribute name="x" type="y" />

An Attribute can appear 0 or 1 times within a given element in the XML document. Attributes are either optional or mandatory (by default they are optional). The "use" property in the XSD definition is used to specify if the attribute is optional or mandatory.

So the following are equivalent:

<xs:attribute name="ID" type="xs:string" /> <xs:attribute name="ID" type="xs:string" use="optional" />

The previous XSD definitions are shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

To specify that an attribute must be present, use = "required" (Note: use may also be set to "prohibited", but we'll come to that later).

An attribute is typically specified within the XSD definition for an element, nesting the attribute in the element. Attributes can also be specified globally and then referenced (but more about this later).

| Sample XSD | Sample XML |

|---|---|

<xs:element name="Order"> <xs:complexType> <xs:attribute name="OrderID" type="xs:int" /> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> | <Order OrderID="6" />- or no attribute - <Order /> |

<xs:element name="Order"> <xs:complexType> <xs:attribute name="OrderID" type="xs:int" use="optional" /> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> | <Order OrderID="6" />- or no attribute - <Order /> |

<xs:element name="Order"> <xs:complexType> <xs:attribute name="OrderID" type="xs:int" use="required" /> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> | <Order OrderID="6" /> |

The default and fixed attributes can be specified within the XSD attribute specification (in the same way as they are for elements).

Using Mixed Content

So far we have seen how an element can contain data, other elements and attributes. Elements can also contain a combination of all of these.

You can also mix elements and data. You can specify this in the XSD schema by setting the mixed property.

You can also mix elements and data. You can specify this in the XSD schema by setting the mixed property.

<xs:element name="MarkedUpDesc"> <xs:complexType mixed="true"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Bold" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Italic" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

A sample XML document could look like this:

<MarkedUpDesc> This is an <Bold>Example</Bold> of <Italic>Mixed</Italic> Content, Note there are elements mixed in with the elements data. </MarkedUpDesc>

Should I use an Element or an Attribute?

It is often confusing when to use an element as opposed to using an attribute within your XML Schema.

Some designers have the opinion that elements describe data whereas attributes describe the Meta data,

others would say that attributes are used for small pieces of data such as an order id, but really it is personal taste with no

hard and fast rules as to when to use an attribute.

Some designers have the opinion that elements describe data whereas attributes describe the Meta data,

others would say that attributes are used for small pieces of data such as an order id, but really it is personal taste with no

hard and fast rules as to when to use an attribute.

A good rule of thumb might be to only use an attribute if it can be considered an aggregate of the parent element that relies on

the parent to make sense. Whereas a child Element may be perfectly happy to exist outside of the parent element, in other words it is a composite item that has a relationship with the parent element.

the parent to make sense. Whereas a child Element may be perfectly happy to exist outside of the parent element, in other words it is a composite item that has a relationship with the parent element.

So an element named Shape may have an attribute named Colour, i.e. Meta data about the Shape, and a child element that represents

a sequence of elements named Point, an independent structure of data.

a sequence of elements named Point, an independent structure of data.

Sample XML Schema (XSD):

<xs:element name="Shape"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Point" minOccurs="1" maxOccurs="unbounded"> <xs:complexType> <xs:attribute name="x" type="xs:int" /> <xs:attribute name="y" type="xs:int" /> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> </xs:sequence> <xs:attribute name="Colour" type="xs:string" /> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

Sample XML:

<Shape Colour="Black"> <Point x="0" y="0" /> <Point x="100" y="0" /> <Point x="50" y="50" /> </Shape>

Using attributes as containers for data will mean you end up creating documents that are difficult to read and maintain, so try to use elements to describe your data.

Some limitations and possible problems with using attributes include:

- Unlike elements, attributes cannot contain multiple values.

- Attributes are not easily expandable to incorporate future changes to the schema.

- Attributes cannot describe structure whereas child elements can contain a whole variety of child structures.

Should I use Mixed Content?

Mixed content is something you should try to avoid when creating your XML schema. It is used extensively on the web as part of the xHTML standard where is makes sense as the tags are marking up the content. However, it is difficult to parse and it can lead to unforeseen complexity in the XML document's data.

Best Practices when Writing XML Schema (XSD)

- All Element and attributes should use Upper Camel Case (UCC), e.g. (PostalAddress), and should avoid hyphens, spaces or other syntax.

- Readability is more important than tag length up to a point. There is always a line to draw between document size and readability, wherever possible favour readability.

- Avoid abbreviations and acronyms for element, attribute, and type names. Exceptions should be well known within your business area e.g. ID (Identifier), and POS (Point of Sale).

- Postfix all types with the name 'Type', e.g. AddressType. Several standards include Elements and ComplexTypes with the same name which leads to confusion.

- Enumerations should use names not numbers and the values should again be UCC.

- Names should not include the name of the containing structure, e.g. CustomerName should be Name within the parent element Customer.

- Only produce complexTypes or simpleTypes for types that are likely to be re-used. If the structure will only exists in one place define it inline with an anonymous complexType.

- Avoid the use of mixed content.

- Only define root level elements if the element is capable of being the root element in an XML document. If you want the element to have Global scope, create a root level ComplexType or SimpleType instead.

- Use consistent namespace aliases and avoid using the standard defined prefix:

- xml (defined in XML standard)

- xmlns (defined in Namespaces in XML standard)

- xs (defined as http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema)

- xsi (defined as http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance)

- Try to think about versioning early on in your schema design. If its important for a new versions of a schema to be backwardly compatible, then all additions to the schema should be optional. If it is important that existing products should be able to read newer versions of a given document, then consider adding any and anyAttribute entries to the end of your definitions. See Versioning recommendations.

- Define a targetNamespace in your schema, this better identifies your schema and can make things easier to modularize and re-use.

- Set elementFormDefault="qualified" in the schema element of your schema. This makes qualifying the name spaces in the resulting XML simpler to read.

- Using an XML Schema Editor will help you to produce valid XML schema saving you a lot of time.

Extending Complex Types

It is possible to take an existing <xs:complexType> and extend it. Let's see how this may be useful with an example.

Looking at the AddressType that we defined earlier (in Part 1), let's assume our company has now gone international and we need to capture country specific addresses. In this case we need specific information for UK addresses (County and Postcode), and for US addresses (State and ZipCode).

So we can take our existing definition of address and extend it as follows:

<xs:complexType name="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> <xs:complexType name="UKAddressType"> <xs:complexContent> <xs:extension base="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="County" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Postcode" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:extension> </xs:complexContent> </xs:complexType> <xs:complexType name="USAddressType"> <xs:complexContent> <xs:extension base="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="State" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Zipcode" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:extension> </xs:complexContent> </xs:complexType>

Notice each of the two new address types extend the original 'base' address type using:

<xs:extension base="AddressType">

The newly introduced construct <xs:extension> indicates that we are extending an existing type, and specifies the type itself. There is also another new construct, the <xs:complexContent> element, which is just a container for the extension.

So to reiterate, we are defining a new <xs:complexType> called "USAddressType", this extends the existing type "AddressType", and adds to it a sequence containing the elements "State", and "Zipcode".

This is clearer when viewed graphically:

We can now use these new types as follows:

<xs:element name="UKAddress" type="UKAddressType" /> <xs:element name="USAddress" type="USAddressType" />

Sample XML for these elements may look like this:

<UKAddress> <Line1>34 thingy street</Line1> <Line2>someplace</Line2> <County>somerset/County> <Postcode>w1w8uu</Postcode> </UKAddress> <USAddress> <Line1>234 Lancaster Av</Line1> <Line2>Smallville</Line2> <State>Florida</State> <Zipcode>34543</Zipcode> </USAddress>

Restricting Complex Types

The previous section showed how to take an existing <xs:complexType> definition, and extend it to create new types. But there is another option here,

instead of adding to the type, we could restrict it.

instead of adding to the type, we could restrict it.

Taking the same AddressType example, we can create a new type called "InternalAddressType". Let's assume "InternalAddressType" only needs

Address->Line1.

Address->Line1.

<xs:complexType name="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" minOccurs="0" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> <xs:complexType name="InternalAddressType"> <xs:complexContent> <xs:restriction base="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:restriction> </xs:complexContent> </xs:complexType>

Notice the new address type restricts the original 'base' address type using:

<xs:restriction base="AddressType">

We are defining a new type "InternalAddressType". The <xs:restriction> element says we are restricting the existing type "AddressType" ,

and we are only allowing the existing child element "Line1" to be used in this new definition. The <xs:complexContent> element is just

a container for the restriction.

and we are only allowing the existing child element "Line1" to be used in this new definition. The <xs:complexContent> element is just

a container for the restriction.

We also need to make a small modification to the base type as Derivation by restriction does not allow you to add or omit elements

(unless they are optional in the base type), it simply allows you to restrict their valid values e.g. set a default value or

set type="string" where previously no type was specified. So we must change "Line2" to have minOccurs="0".

(unless they are optional in the base type), it simply allows you to restrict their valid values e.g. set a default value or

set type="string" where previously no type was specified. So we must change "Line2" to have minOccurs="0".

Note: As we are restricting an existing type the only definitions that can appear in the <xs:restriction>

are a sub set of the ones defined in the base type "AddressType". They must also be enclosed in the same

compositor (in this case a sequence) and appear in the same order.

are a sub set of the ones defined in the base type "AddressType". They must also be enclosed in the same

compositor (in this case a sequence) and appear in the same order.

We can now use this new type as follows:

<xs:element name="InternalAddress" type="InternalAddressType" />

Sample XML for this element may look like this:

<InternalAddressType> <Line1>Desk 4, Second Floor/<Line1> </InternalAddressType>

Using the xsi:type Attribute

We have just shown how we can create new types based on existing one. This in itself is pretty useful, and will potentially reduce

the amount of complexity in your schemas, making them easier to maintain and understand. However there is an aspect to this

that has not yet been covered. In the above examples we created 3 new types (UKAddressType, USAddressType and InternalAddressType),

all based on AddressType.

the amount of complexity in your schemas, making them easier to maintain and understand. However there is an aspect to this

that has not yet been covered. In the above examples we created 3 new types (UKAddressType, USAddressType and InternalAddressType),

all based on AddressType.

So, if we have an element that explicitly specifies it is of type "UKAddressType", then "UKAddressType" is what must appear in the XML document.

But if an element specifies its of type "AddressType", then any of the 4 types can appear in the XML document

(UKAddressType, USAddressType, InternalAddressType or AddressType). The thing to consider now is,

how will the XML parser know which type you meant to use, surely it needs to know otherwise it can not do proper validation?

(UKAddressType, USAddressType, InternalAddressType or AddressType). The thing to consider now is,

how will the XML parser know which type you meant to use, surely it needs to know otherwise it can not do proper validation?

Well, it knows because if you want to use a type other than the one explicitly specified in the schema (in this case "AddressType") then you have to let the parser know which type your using. This is done in the XML document using the xsi:type attribute.

Let's look at an example:

<xs:element name="Person"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Name" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="HomeAddress" type="AddressType" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

Sample XML for the above may look like the following:

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <Person> <Name>Fred</Name> <HomeAddress> <Line1>22 whatever place, someplace</Line1> <Line2>sometown, ss1 6gy </Line2> </HomeAddress> </Person>

However, the following is also valid:

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <Person xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"> <Name>Fred</Name> <HomeAddress xsi:type="USAddressType"> <Line1>234 Lancaseter Av</Line1> <Line2>SmallsVille</Line2> <State>Florida</State> <Zipcode>34543</Zipcode> </HomeAddress> </Person>

Let's look at that in more detail.

- We have added the attribute xsi:type="USAddressType" to the "HomeAddress" element. This tells the XML parser that the element actually contains data described by "USAddressType".

- The xmlns:xsi attribute in the root element (Person) tells the XML parser that the alias xsi maps to the namespace "http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance".

- The xsi: part of the xsi:type attribute is a namespace qualifier. It basically says the attribute "type" is from the namespace that is aliased by "xsi" which was defined earlier to mean "http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance".

- The "type" attribute in this namespace is an instruction to the XML Parser to tell it which definition to use to validate the element.

We'll learn more about namespaces in the next section.

Extending Simple Types

There are 3 ways in which a simpleType can be extended; Restriction, List and Union. The most common is Restriction, but we will cover the other 2 as well.

Restriction

Restriction is a way to constrain an existing type definition. We can apply a restriction to the built in data types xs:string, xs:integer, xs:date, etc. or ones we create ourselves.

Here we are defining a restriction the existing type "string", we are applying a regular expression to it, to limit the values it can take.

<xs:simpleType name="LetterType"> <xs:restriction base="xs:string"> <xs:pattern value="[a-zA-Z]" /> </xs:restriction> </xs:simpleType>

This can be shown graphically in Liquid Studio as follows:

Let's go through this line by line.

- 1.A <simpleTyp> tag is used to define a our new type, we must give the type a unique name - in this case "LetterType".

- 2.We are restricting an existing type - so the tag is <restriction> (you can also extend an existing type - but more about this later). We are basing our new type on a string so type="xs:string".

- 3.We are applying a restriction in the form of a Regular expression, this is specified using the <pattern> element. The regular expression means the data must contain a single lower or upper case letter a through to z.

- 4.closing tag for the restriction.

- 5.closing tag for the simple type.

Restrictions may also be referred to as Facets. For a complete list see the W3C XSD Standard, but to give you an idea, here are a few examples:

| Overview | Syntax | Syntax explained |

|---|---|---|

| The minimum and maximum length allowed. | <xs:minLength value="3"> <xs:maxLength value="8"> | In this example the length must be between 3 and 8. |

| The lower and upper range for numerical values. | <xs:minInclusive value="0"> <xs:maxInclusive value="10"> | The value must be between 0 and 10. |

| The lower and upper range for numerical values. | <xs:minExclusive value="0"> <xs:maxExclusive value="10"> | The value must be between 1 and 9. |

| The exact number of characters allowed. | <xs:length value="30"> | The length must be exactly 30 characters. |

| The maximum number of digits allowed. | <xs:totalDigits value="9"> | The value must have no more than 9 digits. |

| The maximum number of decimal places allowed. | <xs:fractionDigits value="2"> | The value must have no more than 2 decimal places. |

| A list of values allowed. | <xs:enumeration value="Hippo"> <xs:enumeration value="Zebra"> <xs:enumeration value="Lion"> | The only permitted values are Hippo, Zebra or Lion. |

| This defines how whitespace will be handled (e.g. line feeds, carriage returns, tabs, spaces). | <xs:whitespace value="preserve"> <xs:whitespace value="replace"> <xs:whitespace value="collapse"> | Preserve - Keeps all whitespace. Replace - Replaces each whitespace with a space. Collapse - Replaces each whitespace character with a space and then reduces multiple spaces to one space. |

| Defines the character pattern allowed using regular expressions. For a complete list see the W3C XSD Standard: Regular Expressions. | <xs:pattern value="[0-9]"> | [0-9] - 1 digit only between 0 and 9. [0-9][0-9][0-9] - 3 digits all have to be between 0 and 9. [a-z][0-9][A-Z] - 1st digit has to be between a and z and 2nd digit has to be between 0 and 9 and the 3rd digit is between A and Z. These are case sensitive. [a-zA-Z] - 1 digit that can be either lower or upper case A to Z. [123] - 1 digit that has to be 1, 2 or 3. ([a-z])* - Zero or more occurrences of a to z. ([q][u])+ - Looking for a pair letters that satisfy the criteria, in this case a q followed by a u. ([a-z][0-9])+ - As above, looking for a pair where the 1st digit is lower case and between a and z, and the 2nd digit is between 0 and 9, for example a1, c2, z159, f45. [a-z0-9]{8} - Must be exactly 8 characters in a row and they must be lower case a to z or number 0 to 9. |

It is important to note that not all facets are valid for all data types - for example, maxInclusive has no meaning when applied to a string. For the combinations of facets that are valid for a given data type refer to the W3C XSD standard.

Union

A union is a mechanism for combining two or more different data types into one.

The following defines two simple types "SizeByNumberType" all the positive integers up to 21 (e.g. 10, 12, 14), and "SizeByStringNameType" the values small, medium and large.

<xs:simpleType name="SizeByNumberType"> <xs:restriction base="xs:positiveInteger"> <xs:maxInclusive value="21" /> </xs:restriction> </xs:simpleType> <xs:simpleType name="SizeByStringNameType"> <xs:restriction base="xs:string"> <xs:enumeration value="small" /> <xs:enumeration value="medium" /> <xs:enumeration value="large" /> </xs:restriction> </xs:simpleType>

We can then define a new type called "USClothingSizeType", we define this as a union of the types "SizeByNumberType" and "SizeByStringNameType" (although we can add any number of types, including the built in types - separated by whitespace).

<xs:simpleType name="USClothingSizeType"> <xs:union memberTypes="SizeByNumberType SizeByStringNameType" /> </xs:simpleType>

This means the type can contain any of the values that the two members can take (e.g. 1, 2, 3, ...., 20, 21, small, medium, large).

This new type can then be used in the same way as any other <xs:simpleType>.

List

A list allows the value (in the XML document) to contain a number of valid values separated by whitespace.

A List is constructed in a similar way to a Union. The difference being that we can only specify a single type. This new type can contain a list of values that are defined by the itemType property. The values must be whitespace separated. So a valid value for this type would be "5 9 21".

<xs:simpleType name="SizesinStockType"> <xs:list itemType="SizeByNumberType" /> </xs:simpleType>

Namespaces Overview

So far in this tutorial we have largely ignored namespaces as they are an added complexity over writing and using basic XSDs. The full set of namespace rules are very complex, be this overview will provide a basic outline of the technology. If you are creating and modifying XML documents validating against XML Schema making use of namespaces, then XML Data Binding will save you a great deal of time as mostly removes this complexity. If you choose not to use an XML Data Binding tool, you may be advised to refer to the XSD standard and invest in a good book regarding XML Schema.

Namespaces are a mechanism for breaking up your schemas. Up until now we have assumed that you only have a single schema file containing all your element definitions, but the XSD standard allows you to structure your XSD schemas by breaking them into multiple files. These child schemas can then be included into a parent schema.

Breaking schemas into multiple files can have several advantages. You can create re-usable definitions that can be used across several projects. They make definitions easier to read and version as they break down the schema into smaller units that are simpler to manage.

Namespace Walk-through Example

In this example, the schema is broken out into four files:

- CommonTypes - this could contain all your basic types such as AddressType, PriceType, and PaymentMethodType

- CustomerTypes - this could contain all your definitions for your customers.

- OrderTypes - this could contain all your definitions for orders.

- Main - this would pull all the sub schemas together into a single schema, and define your main elements.

This all works fine without namespaces, but if different teams start working on different files, then you have the possibility of name clashes, and it would not always be obvious where a definition had come from. The solution is to place the definitions for each schema file within a distinct namespace.

We can do this by adding the attribute targetNamespace into the schema element in the XSD file:

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <xs:schema xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" targetNamespace="myNamespace"> ... </xs:schema>

The value of targetNamespace is simply a unique identifier, typically a company may use their URL followed by something descriptive to qualify it.

In principle the namespace has no meaning, but some companies have used the URL where the schema is stored as the targetNamespace, and so some XML parsers will use this as a hint path for the schema:

targetNamespace="http://www.microsoft.com/CommonTypes.xsd"

However, the following would be equally valid:

targetNamespace="my-common-types"

Placing the targetNamespace attribute at the top of your XSD schema means that all entities defined in it are part of this namespace. So in our example above each of the 4 schema files could have a distinct targetNamespace value.

Let's look at them in detail.

CommonTypes.xsd

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-16" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <xs:schema targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" elementFormDefault="qualified"> <xs:complexType name="AddressType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Line1" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Line2" type="xs:string" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> <xs:simpleType name="PriceType"> <xs:restriction base="xs:decimal"> <xs:fractionDigits value="2" /> </xs:restriction> </xs:simpleType> <xs:simpleType name="PaymentMethodType"> <xs:restriction base="xs:string"> <xs:enumeration value="VISA" /> <xs:enumeration value="MasterCard" /> <xs:enumeration value="Cash" /> <xs:enumeration value="AMEX" /> </xs:restriction> </xs:simpleType> </xs:schema>

This schema defines some basic re-usable entities and types. The use of the targetNamespace attribute in the <xs:schema> element ensures all the enclosed definitions (AddressType, PriceType and PaymentMethodType) are all in the namespace:

targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes"

CustomerTypes.xsd

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-16" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <xs:schema xmlns:cmn="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes" xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" elementFormDefault="qualified"> <xs:import schemaLocation="CommonTypes.xsd" namespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" /> <xs:complexType name="CustomerType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Name" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="DeliveryAddress" type="cmn:AddressType" /> <xs:element name="BillingAddress" type="cmn:AddressType" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:schema>

This schema defines the entity CustomerType, which makes use of the AddressType defined in the CommonTypes.xsd schema. We need to do a few things in order to use this.

First we need to import that schema into this one - so we can see it. This is done using <xs:import>. It is worth noting the presence of the targetNamespace attribute at this point. This means that all entities defined in this schema belong to that namespace:

targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes"

So in order to make use of the AddressType which is defined in CommonTypes.xsd, and part of the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes", we must fully qualify it.

In order to do this we must define an alias for the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes", we do this by adding another attribute in the <xs:schema> element:

xmlns:cmn="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes"

This specifies that the alias "cmn" represents the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes". We can now make use of the types within the CommonTypes.xsd schema. When we do this we must fully qualify them as they are not in the same targetNamespace as the schema that is using them:

<xs:element name="DeliveryAddress" type="cmn:AddressType" /> <xs:element name="BillingAddress" type="cmn:AddressType" />

OrderType.xsd

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-16" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <xs:schema xmlns:cmn="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes" xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" elementFormDefault="qualified"> <xs:import schemaLocation="CommonTypes.xsd" namespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" /> <xs:complexType name="OrderType"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element maxOccurs="unbounded" name="Item"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="ProductName" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Quantity" type="xs:int" /> <xs:element name="UnitPrice" type="cmn:PriceType" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:schema>

This schema defines the type OrderType which is within the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes":

targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes"

The constructs used here are the same as those used in CustomerTypes.xsd.

Main.xsd

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-16" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <xs:schema xmlns:ord="http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes" xmlns:pur="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase" xmlns:cmn="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" xmlns:cust="http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes" targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase" xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema" elementFormDefault="qualified"> <xs:import schemaLocation="CommonTypes.xsd" namespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes" /> <xs:import schemaLocation="CustomerTypes.xsd" namespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes" /> <xs:import schemaLocation="OrderTypes.xsd" namespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes" /> <xs:element name="Purchase"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="OrderDetail" type="ord:OrderType" /> <xs:element name="PaymentMethod" type="cmn:PaymentMethodType" /> <xs:element ref="pur:CustomerDetails" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> <xs:element name="CustomerDetails" type="cust:CustomerType" /> </xs:schema>

The elements in this schema are part of the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase":

targetNamespace="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase"

This is our main schema and defines the concrete elements "Purchase", and "CustomerDetails". This element builds on the other schemas, so we need to import them all, and define aliases for each namespace.

Note: The element "CustomerDetails" which is defined in main.xsd is referenced from within "Purchase".

XML Document

As the root element "Purchase" is in the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase", we must quantify the <Purchase> element within the resulting XML document. Let's look at an example:

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <p:Purchase xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase Main.xsd" xmlns:p="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase" xmlns:o="http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes" xmlns:c="http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes" xmlns:cmn="http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes"> <p:OrderDetail> <o:Item> <o:ProductName>Widget</o:ProductName> <o:Quantity>1</o:Quantity> <o:UnitPrice>3.42</o:UnitPrice> </o:Item> </p:OrderDetail> <p:PaymentMethod>VISA</p:PaymentMethod> <p:CustomerDetails> <c:Name>James</c:Name> <c:DeliveryAddress> <cmn:Line1>15 Some Road</cmn:Line1> <cmn:Line2>SomeTown</cmn:Line2> </c:DeliveryAddress> <c:BillingAddress> <cmn:Line1>15 Some Road</cmn:Line1> <cmn:Line2>SomeTown</cmn:Line2> </c:BillingAddress> </p:CustomerDetails> </p:Purchase>

The first thing we see is the xsi:schemaLocation attribute in the root element. This tells the XML parser that elements within the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase" can be found in the file "Main.xsd" (Note: the namespace and URL are separated with whitespace, such as a carriage return or space).

The next thing we do is define some aliases:

- "p" to mean the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase"

- "c" to mean the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/CustomerTypes"

- "o" to mean the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes"

- "cmn" to mean the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/CommonTypes"

You have probably noticed that every element in the schema is qualified with one of these aliases. The general rules for this are:

The alias must be the same as the target namespace in which the element is defined. It is important to note that this is where the element is defined - not where the complexType is defined.

So the element <OrderDetail> is actually defined in main.xsd and so it is part of the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase", even though it uses the complexType "OrderType" which is defined in the OrderTypes.xsd. The contents of <OrderDetail> are defined within the complexType "OrderType", which is in the target namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes", so the child element <Item> needs qualifying within the namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/OrderTypes".

The elementFormDefault Attribute

You may have noticed that each schema contained an attribute elementFormDefault="qualified". This has two possible values, qualified, and unqualified, the default is unqualified. This attribute changes the namespace rules considerably. It is normally easier to set it to qualified.

So to see the effects of this property, if we set it to be unqualified in all of our schemas, the resulting XML would look like this:

<?xml version="1.0" ?> <!-- Created with Liquid Studio (http://www.liquid-technologies.com) --> <p:Purchase xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase Main.xsd" xmlns:p="http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase"> <OrderDetail> <Item> <ProductName>Widget</ProductName> <Quantity>1</Quantity> <UnitPrice>3.42</UnitPrice> </Item> </OrderDetail> <PaymentMethod>VISA</PaymentMethod> <p:CustomerDetails> <Name>James</Name> <DeliveryAddress> <Line1>15 Some Road</Line1> <Line2>SomeTown</Line2> </DeliveryAddress> <BillingAddress> <Line1>15 Some Road</Line1> <Line2>SomeTown</Line2> </BillingAddress> </p:CustomerDetails> </p:Purchase>

This is considerably different from the previous XML document. These general rules now apply:

- Only root elements defined within a schema need qualifying with a namespace.

- All types that are defined inline do NOT need to be qualified.

The first element is Purchase, this is defined globally in the Main.xsd schema, and therefore needs qualifying within the schemas target namespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase".

The first child element is <OrderDetail> and is defined inline in Main.xsd->Purchase. So it does not need to be aliased.

The same is true for all the child elements, they are all defined inline, so they do not need qualifying with a namespace.

The final child element <CustomerDetails> is a little different. As you can see we have defined this as a global element within the targetNamespace "http://NamespaceTest.com/Purchase". In the element "Purchase" we just reference it. Because we are using a reference to an element, we must take into account its namespace, thus we alias it <p:CustomerDetails>.

Element and Attribute Groups

Elements and Attributes can be grouped together using <xs:group> and <xs:attributeGroup>. These groups can then be referred to elsewhere within the schema. Groups must have a unique name and be defined as children of the <xs:schema> element. When a group is referred to, it is as if its contents have been copied into the location it is referenced from.

Note: <xs:group> and <xs:attributeGroup> can not be extended or restricted in the way <xs:complexType> or <xs:simpleType> can. They are purely to group a number of items of data that are always used together. For this reason they are not the first choice of constructs for building reusable maintainable schemas, but they can have their uses.

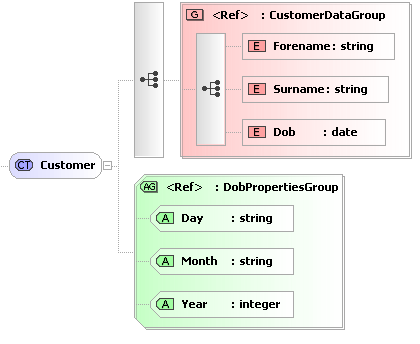

<xs:group name="CustomerDataGroup"> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="Forename" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Surname" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Dob" type="xs:date" /> </xs:sequence> </xs:group> <xs:attributeGroup name="DobPropertiesGroup"> <xs:attribute name="Day" type="xs:string" /> <xs:attribute name="Month" type="xs:string" /> <xs:attribute name="Year" type="xs:integer" /> </xs:attributeGroup>

These groups can then be referenced in the definition of complex types, as shown below:

<xs:complexType name="Customer"> <xs:sequence> <xs:group ref="CustomerDataGroup" /> <xs:element name="..." type="..." /> </xs:sequence> <xs:attributeGroup ref="DobPropertiesGroup" /> </xs:complexType>

The <any> Element

The <any> construct allows us specify that our XML document can contain elements that are not defined in this schema. A typical use for this is when you define a message envelope. For example, the message payload is unknown to the system, but we can still validate the message.

Look at the following schema:

<xs:element name="Message"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:element name="DateSent" type="xs:date" /> <xs:element name="Sender" type="xs:string" /> <xs:element name="Content"> <xs:complexType> <xs:sequence> <xs:any /> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element> </xs:sequence> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

We have defined an element called "Message", which must have a "DateSent" child element (which is a date), a "Sender" child element (which must be a string), and a "Content" child element - which can contain any element - it doesn't even have to be described in the schema.

So the following XML would be acceptable.

<Message> <DateSent>2000-01-12</DateSent> <Sender>Admin</Sender> <Content> <AccountCreationRequest> <AccountName>Fred</AccountName> </AccountCreationRequest> </Content> </Message>

The <any> construct has a number of properties that can further restrict what can be used in its place.

minOccurs and maxOccurs allows you to specify how may instances of undefined elements must be placed within the XML document.

namespace allows you to specify that the undefined element must belong to a given namespace. This may be a list of namespace's (space separated). There are also three built in values ##any, ##other, ##targetnamespace, ##local. Consult the XSD standard for more information on this.

processContents tells the XML parser how to deal with the unknown elements. The values are:

- Skip - no validation is performed - but it must be well formed XML.

- Lax - if there is a schema to validate the element, then it must be valid against it, if there is no schema, then that's OK.

- Strict - There must be a definition for the element available to the parser, and it must be valid against it.

The <anyAttribute> Element

<anyAttribute> works in the same way as <any>, except it allows unknown attributes to be inserted into a given element.

<xs:element name="Sender"> <xs:complexType> <xs:simpleContent> <xs:extension base="xs:string"> <xs:anyAttribute /> </xs:extension> </xs:simpleContent> </xs:complexType> </xs:element>

This would mean that we can add any attributes we like to the Sender element, and the XML document would still be valid:

<Sender ID="7687">Fred</Sender>

No comments:

Post a Comment